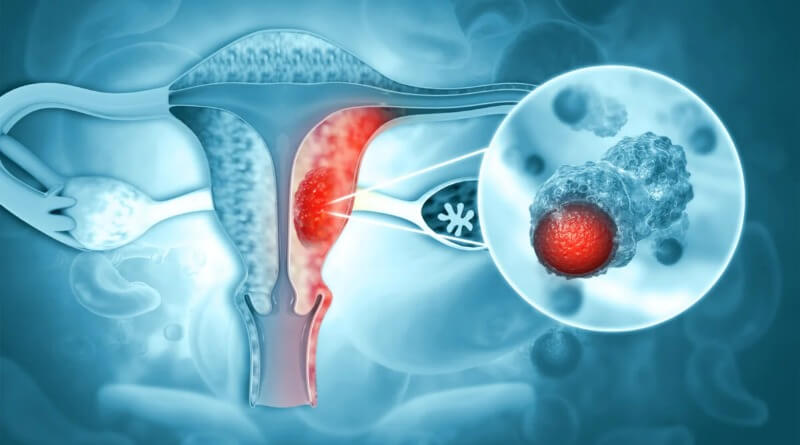

Endometrial cancer refers to several types of malignancies that arise from the endometrium, or lining, of the uterus. Endometrial cancers are the most common gynecologic cancers in the United States, with over 35,000 women diagnosed each year. The most common subtype, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, typically occurs within a few decades of menopause, is associated with excessive estrogen exposure, often develops in the setting of endometrial hyperplasia, and presents most often with vaginal bleeding. Endometrial carcinoma is the third most common cause of gynecologic cancer death (behind ovarian and cervical cancer). A total abdominal hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the most common therapeutic approach.

Endometrial cancer may sometimes be referred to as uterine cancer. However, different cancers may develop not only from the endometrium itself but also from other tissues of the uterus, including cervical cancer, sarcoma of the myometrium, and trophoblastic disease.

What are the Causes for Endometrial Cancer?

Healthy cells grow and divide in an orderly way to keep your body functioning normally. But sometimes cells become abnormal (mutate) and grow out of control. The cells continue dividing even when new cells aren’t needed. These abnormal cells can invade and destroy nearby tissues and even have the ability to travel to other parts of the body and begin growing there.

In endometrial cancer, cancer cells develop in the lining of the uterus. Why these cancer cells develop isn’t entirely known. However, scientists believe that estrogen levels play a role in the development of endometrial cancer. Factors that can increase the levels of this hormone and other risk factors for the disease have been identified and continue to emerge. In addition, ongoing research is devoted to studying changes in certain genes that may cause the cells in the endometrium to become cancerous.

What are the Risk Factors?

No one knows the exact causes of uterine cancer. However, it is clear that this disease is not contagious. No one can “catch” cancer from another person.

Women who get this disease are more likely than other women to have certain risk factors. A risk factor is something that increases a person’s chance of developing the disease.

Most women who have known risk factors do not get uterine cancer. On the other hand, many who do get this disease have none of these factors. Doctors can seldom explain why one woman gets uterine cancer and another does not.

Studies have found the following risk factors:

- Age. Cancer of the uterus occurs mostly in women over age 50.

- Endometrial hyperplasia. The risk of uterine cancer is higher if a woman has endometrial hyperplasia. This condition and its treatment are described above.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT). HRT is used to control the symptoms of menopause, to prevent osteoporosis (thinning of the bones), and to reduce the risk of heart disease or stroke.

Women who use estrogen without progesterone have an increased risk of uterine cancer. Long-term use and large doses of estrogen seem to increase this risk. Women who use a combination of estrogen and progesterone have a lower risk of uterine cancer than women who use estrogen alone. The progesterone protects the uterus.

Women should discuss the benefits and risks of HRT with their doctor. Also, having regular checkups while taking HRT may improve the chance that the doctor will find uterine cancer at an early stage, if it does develop. - Obesity and related conditions. The body makes some of its estrogen in fatty tissue. That’s why obese women are more likely than thin women to have higher levels of estrogen in their bodies. High levels of estrogen may be the reason that obese women have an increased risk of developing uterine cancer. The risk of this disease is also higher in women with diabetes or high blood pressure (conditions that occur in many obese women).

- Tamoxifen. Women taking the drug tamoxifen to prevent or treat breast cancer have an increased risk of uterine cancer. This risk appears to be related to the estrogen-like effect of this drug on the uterus. Doctors monitor women taking tamoxifen for possible signs or symptoms of uterine cancer.

The benefits of tamoxifen to treat breast cancer outweigh the risk of developing other cancers. Still, each woman is different. Any woman considering taking tamoxifen should discuss with the doctor her personal and family medical history and her concerns. - Race. White women are more likely than African-American women to get uterine cancer.

- Colorectal cancer. Women who have had an inherited form of colorectal cancer have a higher risk of developing uterine cancer than other women.

Other risk factors are related to how long a woman’s body is exposed to estrogen. Women who have no children, begin menstruation at a very young age, or enter menopause late in life are exposed to estrogen longer and have a higher risk.

Women with known risk factors and those who are concerned about uterine cancer should ask their doctor about the symptoms to watch for and how often to have checkups. The doctor’s advice will be based on the woman’s age, medical history, and other factors.

What are the Symptoms of Endometrial Cancer?

Uterine cancer usually occurs after menopause. But it may also occur around the time that menopause begins. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom of uterine cancer. Bleeding may start as a watery, blood-streaked flow that gradually contains more blood. Women should not assume that abnormal vaginal bleeding is part of menopause.

A woman should see her doctor if she has any of the following symptoms:

- Unusual vaginal bleeding or discharge

- Difficult or painful urination

- Pain during intercourse

- Pain in the pelvic area

These symptoms can be caused by cancer or other less serious conditions. Most often they are not cancer, but only a doctor can tell for sure.

Classification

Carcinoma

Most endometrial cancers are carcinomas (usually adenocarcinomas), meaning that they originate from the single layer of epithelial cells that line the endometrium and form the endometrial glands. There are many microscopic subtypes of endometrial carcinoma, including the common endometrioid type, in which the cancer cells grow in patterns reminiscent of normal endometrium, and the far more aggressive papillary serous carcinoma and clear cell endometrial carcinomas. Some authorities have proposed that endometrial carcinomas be classified into two pathogenetic groups:

- Type I: These cancers occur most commonly in pre- and peri-menopausal women, often with a history of unopposed estrogen exposure and/or endometrial hyperplasia. They are often minimally invasive into the underlying uterine wall, are of the low-grade endometrioid type, and carry a good prognosis.

- Type II: These cancers occur in older, post-menopausal women, are more common in African-Americans, are not associated with increased exposure to estrogen, and carry a poorer prognosis. They include:

- the high-grade endometrioid cancer,

- the uterine papillary serous carcinoma,

- the uterine clear cell carcinoma.

Sarcoma

In contrast to endometrial carcinomas, the uncommon endometrial stromal sarcomas are cancers that originate in the non-glandular connective tissue of the endometrium. Uterine carcinosarcoma, formerly called Malignant mixed müllerian tumor, is a rare uterine cancer that contains cancerous cells of both glandular and sarcomatous appearance – in this case, the cell of origin is unknown.

Diagnosis

If a woman has symptoms that suggest uterine cancer, her doctor may check general signs of health and may order blood and urine tests. The doctor also may perform one or more of the exams or tests described on the next pages.

- Pelvic exam — A woman has a pelvic exam to check the vagina, uterus, bladder, and rectum. The doctor feels these organs for any lumps or changes in their shape or size. To see the upper part of the vagina and the cervix, the doctor inserts an instrument called a speculum into the vagina.

- Pap test — The doctor collects cells from the cervix and upper vagina. A medical laboratory checks for abnormal cells. Although the Pap test can detect cancer of the cervix, cells from inside the uterus usually do not show up on a Pap test. This is why the doctor collects samples of cells from inside the uterus in a procedure called a biopsy.

- Transvaginal ultrasound — The doctor inserts an instrument into the vagina. The instrument aims high-frequency sound waves at the uterus. The pattern of the echoes they produce creates a picture. If the endometrium looks too thick, the doctor can do a biopsy.

- Biopsy — The doctor removes a sample of tissue from the uterine lining. This usually can be done in the doctor’s office. In some cases, however, a woman may need to have a dilation and curettage (D&C). A D&C is usually done as same-day surgery with anesthesia in a hospital. A pathologist examines the tissue to check for cancer cells, hyperplasia, and other conditions. For a short time after the biopsy, some women have cramps and vaginal bleeding.

Pathology

The histopathology of endometrial cancers is highly diverse. The most common finding is a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is composed of numerous, small, crowded glands with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and stratification. This often appears on a background of endometrial hyperplasia. Frank adenocarcinoma may be distinguished from atypical hyperplasia by the finding of clear stromal invasion, or “back-to-back” glands which represent nondestructive replacement of the endometrial stroma by the cancer. With progression of the disease, the myometrium is infiltrated. However, other subtypes of endometrial cancer exist and carry a less favorable diagnosis such as the uterine papillary serous carcinoma and the clear cell carcinoma.

Further evaluation

Patients with newly-diagnosed endometrial cancer do not routinely undergo imaging studies, such as CT scans, to evaluate for extent of disease, since this is of low yield. Preoperative evaluation should include a complete medical history and physical examination, pelvic examination and rectal examination with stool guaiac test, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and blood chemistry tests, including liver function tests. Colonoscopy is recommended if the stool is guaiac positive or the woman has symptoms, due to the etiologic factors common to both endometrial cancer and colon cancer. The tumor marker CA-125 is sometimes checked, since this can predict advanced stage disease. In addition to this, both D&C and Pipelle biopsy curettage give 65-70% positive predictive value. But most important of these is hysteroscopy which gives 90-95% positive predictive value.

Staging

Endometrial carcinoma is surgically staged using the FIGO cancer staging system. Although the FIGO staging has recently been updated, the older staging described below is still commonly used.

- Stage IA: tumor limited to the endometrium

- Stage IB: invasion of less than half the myometrium

- Stage IC: invasion of more than half the myometrium

- Stage IIA: endocervical glandular involvement only

- Stage IIB: cervical stromal invasion

- Stage IIIA: tumor invades serosa or adnexa, or malignant peritoneal cytology

- Stage IIIB: vaginal metastasis

- Stage IIIC: metastasis to pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes

- Stage IVA: invasion of the bladder or bowel

- Stage IVB: distant metastasis, including intraabdominal or inguinal lymph nodes

The 2010 Figo staging system is as follows: Carcinoma of the Endometrium

- IA Tumor confined to the uterus, no or < ½ myometrial invasion

- IB Tumor confined to the uterus, > ½ myometrial invasion

- II Cervical stromal invasion, but not beyond uterus

- IIIA Tumor invades serosa or adnexa

- IIIB Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement

- IIIC1 Pelvic node involvement

- IIIC2 Para-aortic involvement

- IVA Tumor invasion bladder and/or bowel mucosa

- IVB Distant metastases including abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes

Methods of Treatment

Women with uterine cancer have many treatment options. Most women with uterine cancer are treated with surgery. Some have radiation therapy. A smaller number of women may be treated with hormonal therapy. Some patients receive a combination of therapies.

The doctor is the best person to describe the treatment choices and discuss the expected results of treatment.

A woman may want to talk with her doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option for women with all stages of uterine cancer. The section on “The Promise of Cancer Research” has more information about clinical trials.

Most women with uterine cancer have surgery to remove the uterus (hysterectomy) through an incision in the abdomen. The doctor also removes both fallopian tubes and both ovaries. (This procedure is called a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.)

The doctor may also remove the lymph nodes near the tumor to see if they contain cancer. If cancer cells have reached the lymph nodes, it may mean that the disease has spread to other parts of the body. If cancer cells have not spread beyond the endometrium, the woman may not need to have any other treatment. The length of the hospital stay may vary from several days to a week.

In radiation therapy, high-energy rays are used to kill cancer cells. Like surgery, radiation therapy is a local therapy. It affects cancer cells only in the treated area.

Some women with Stage I, II, or III uterine cancer need both radiation therapy and surgery. They may have radiation before surgery to shrink the tumor or after surgery to destroy any cancer cells that remain in the area. Also, the doctor may suggest radiation treatments for the small number of women who cannot have surgery.

Doctors use two types of radiation therapy to treat uterine cancer:

- External radiation: In external radiation therapy, a large machine outside the body is used to aim radiation at the tumor area. The woman is usually an outpatient in a hospital or clinic and receives external radiation 5 days a week for several weeks. This schedule helps protect healthy cells and tissue by spreading out the total dose of radiation. No radioactive materials are put into the body for external radiation therapy.

- Internal radiation: In internal radiation therapy, tiny tubes containing a radioactive substance are inserted through the vagina and left in place for a few days. The woman stays in the hospital during this treatment. To protect others from radiation exposure, the patient may not be able to have visitors or may have visitors only for a short period of time while the implant is in place. Once the implant is removed, the woman has no radioactivity in her body.

Some patients need both external and internal radiation therapies.

Hormonal therapy involves substances that prevent cancer cells from getting or using the hormones they may need to grow. Hormones can attach to hormone receptors, causing changes in uterine tissue. Before therapy begins, the doctor may request a hormone receptor test. This special lab test of uterine tissue helps the doctor learn if estrogen and progesterone receptors are present. If the tissue has receptors, the woman is more likely to respond to hormonal therapy.

Hormonal therapy is called a systemic therapy because it can affect cancer cells throughout the body. Usually, hormonal therapy is a type of progesterone taken as a pill.

The doctor may use hormonal therapy for women with uterine cancer who are unable to have surgery or radiation therapy. Also, the doctor may give hormonal therapy to women with uterine cancer that has spread to the lungs or other distant sites. It is also given to women with uterine cancer that has come back.

Side effects of cancer treatment

Because cancer treatment may damage healthy cells and tissues, unwanted side effects sometimes occur. These side effects depend on many factors, including the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may even change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, doctors and nurses will explain the possible side effects and how they will help you manage them.

Surgery

After a hysterectomy, women usually have some pain and feel extremely tired. Most women return to their normal activities within 4 to 8 weeks after surgery. Some may need more time than that.

Some women may have problems with nausea and vomiting after surgery, and some may have bladder and bowel problems. The doctor may restrict the woman’s diet to liquids at first, with a gradual return to solid food.

Women who have had a hysterectomy no longer have menstrual periods and can no longer get pregnant. When the ovaries are removed, menopause occurs at once. Hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause caused by surgery may be more severe than those caused by natural menopause. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is often given to women who have not had uterine cancer to relieve these problems. However, doctors usually do not give the hormone estrogen to women who have had uterine cancer. Because estrogen is a risk factor for this disease (see “Uterine Cancer: Who’s at Risk?”), many doctors are concerned that estrogen may cause uterine cancer to return. Other doctors point out that there is no scientific evidence that estrogen increases the risk that cancer will come back. NCI is sponsoring a large research study to learn whether women who have had early stage uterine cancer can take estrogen safely.

For some women, a hysterectomy can affect sexual intimacy. A woman may have feelings of loss that may make intimacy difficult. Sharing these feelings with her partner may be helpful.

Radiation therapy

The side effects of radiation therapy depend mainly on the treatment dose and the part of the body that is treated. Common side effects of radiation include dry, reddened skin and hair loss in the treated area, loss of appetite, and extreme tiredness. Some women may have dryness, itching, tightening, and burning in the vagina. Radiation also may cause diarrhea or frequent and uncomfortable urination. It may reduce the number of white blood cells, which help protect the body against infection.

Doctors may advise their patients not to have intercourse during radiation therapy. However, most can resume sexual activity within a few weeks after treatment ends. The doctor or nurse may suggest ways to relieve any vaginal discomfort related to treatment.

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy can cause a number of side effects. Women taking progesterone may retain fluid, have an increased appetite, and gain weight. Women who are still menstruating may have changes in their periods.

Nutrition

People need to eat well during cancer therapy. They need enough calories and protein to promote healing, maintain strength, and keep a healthy weight. Eating well often helps people with cancer feel better and have more energy.

Patients may not feel like eating if they are uncomfortable or tired. Also, the side effects of treatment such as poor appetite, nausea, or vomiting can make eating difficult. Foods may taste different.

The doctor, dietitian, or other health care provider can advise patients about ways to maintain a healthy diet.

Followup care

Followup care after treatment for uterine cancer is important. Women should not hesitate to discuss followup with their doctor. Regular checkups ensure that any changes in health are noticed. Any problem that develops can be found and treated as soon as possible. Checkups may include a physical exam, a pelvic exam, x-rays, and laboratory tests.

Drugs rating:

| Title | Votes | Rating | ||

| 1 | Megace (Megestrol) | 3 |

|

(8.3/10) |

| 2 | Provera (Medroxyprogesterone) | 122 |

|

(6.8/10) |

| 3 | Depo-Provera (Medroxyprogesterone) | 35 |

|

(5.7/10) |

| 4 | Megace Suspension (Megestrol) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

Prognosis

Because endometrial cancer is usually diagnosed in the early stages (70 % to 75 % of cases are in stage 1 at diagnosis; 10 % to 15 % of cases are in stage 2; 10 % to 15 % of cases are in stage 3 or 4), there is a better probable outcome associated with it than with other types of gynecological cancers such as cervical or ovarian cancer. While endometrial cancers are 40% more common in Caucasian women, an African American woman who is diagnosed with uterine cancer is twice as likely to die (possibly due to the higher frequency of aggressive subtypes in that population, but more probable due to delay in the diagnosis).

Survival rates

The 5-year survival rates for endometrial adenocarcinoma following appropriate treatment are:

| Stage | 5 year survival rate |

| I-A | 90% |

| I-B | 88% |

| I-C | 75% |

| II | 69% |

| III-A | 58% |

| III-B | 50% |

| III-C | 47% |

| IV-A | 17% |

| IV-B | 15% |

Support for women with uterine cancer

Living with a serious disease such as cancer is not easy. Some people find they need help coping with the emotional and practical aspects of their disease. Support groups can help. In these groups, patients or their family members get together to share what they have learned about coping with the disease and the effects of treatment. Patients may want to talk with a member of their health care team about finding a support group.

It is natural for a woman to be worried about the effects of uterine cancer and its treatment on her sexuality. She may want to talk with the doctor about possible side effects and whether these effects are likely to be temporary or permanent. Whatever the outlook, it may be helpful for women and their partners to talk about their feelings and help one another find ways to share intimacy during and after treatment.

People living with cancer may worry about caring for their families, holding on to their jobs, or keeping up with daily activities. Concerns about treatments and managing side effects, hospital stays, and medical bills are also common. Doctors, nurses, and other members of the health care team will answer questions about treatment, working, or other activities. Meeting with a social worker, counselor, or member of the clergy can be helpful to those who want to talk about their feelings or discuss their concerns. Often, a social worker can suggest resources for financial aid, transportation, home care, or emotional support.