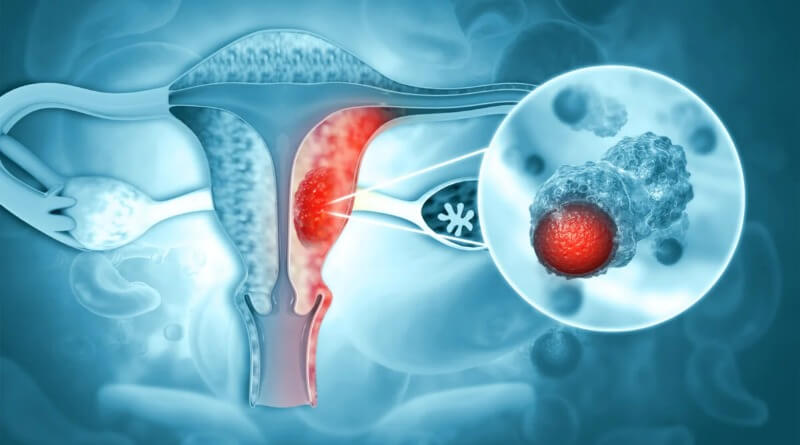

Ovarian cancer is a cancerous growth arising from different parts of the ovary.

Most (>90%) ovarian cancers are classified as “epithelial” and were believed to arise from the surface (epithelium) of the ovary. However, recent evidence suggests that the Fallopian tube could also be the source of some ovarian cancers. Since the ovaries and tubes are closely related to each other, it is hypothesized that these cells can mimic ovarian cancer. Other types arise from the egg cells (germ cell tumor) or supporting cells (sex cord/stromal).

In 2004, in the United States, 25,580 new cases were diagnosed and 16,090 women died of ovarian cancer. The risk increases with age and decreases with pregnancy. Lifetime risk is about 1.6%, but women with affected first-degree relatives have a 5% risk. Women with a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene carry a risk between 25% and 60% depending on the specific mutation. Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of death from cancer in women and the leading cause of death from gynecological cancer.

In early stages ovarian cancer is associated with abdominal distension.

10-year relative survival ranges from 84.1% in stage IA to 10.4% in stage IIIC.

Ovarian cancer causes non-specific symptoms. Early diagnosis would result in better survival, on the assumption that stage I and II cancers progress to stage III and IV cancers (but this has not been proven). Most women with ovarian cancer report one or more symptoms such as abdominal pain or discomfort, an abdominal mass, bloating, back pain, urinary urgency, constipation, tiredness and a range of other non-specific symptoms, as well as more specific symptoms such as pelvic pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding or involuntary weight loss. There can be a build-up of fluid (ascites) in the abdominal cavity.

Diagnosis of ovarian cancer starts with a physical examination (including a pelvic examination), a blood test (for CA-125 and sometimes other markers), and transvaginal ultrasound. The diagnosis must be confirmed with surgery to inspect the abdominal cavity, take biopsies (tissue samples for microscopic analysis) and look for cancer cells in the abdominal fluid. Treatment usually involves chemotherapy and surgery, and sometimes radiotherapy.

In most cases, the cause of ovarian cancer remains unknown. Older women, and in those who have a first or second degree relative with the disease, have an increased risk. Hereditary forms of ovarian cancer can be caused by mutations in specific genes (most notably BRCA1 and BRCA2, but also in genes for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer). Infertile women and those with a condition called endometriosis, those who have never been pregnant and those who use postmenopausal estrogen replacement therapy are at increased risk. Use of combined oral contraceptive pills is a protective factor. The risk is also lower in women who have had their uterine tubes blocked surgically (tubal ligation).

What causes Ovarian Cancer?

The exact cause is usually unknown. The risk of developing ovarian cancer appears to be affected by several factors. The more children a woman has, the lower her risk of ovarian cancer. Early age at first pregnancy, older age of final pregnancy and the use of low dose hormonal contraception have also been shown to have a protective effect.

Hormones

The relationship between use of oral contraceptives and ovarian cancer was shown in a summary of results of 45 case-control and prospective studies. Cumulatively these studies show a protective effect for ovarian cancers. Women who used oral contraceptives for 10 years had about a 60% reduction in risk of ovarian cancer. (risk ratio .42 with statistical significant confidence intervals given the large study size, not unexpected). This means that if 250 women took oral contraceptives for 10 years, 1 ovarian cancer would be prevented. This is by far the largest epidemiological study to date on this subject (45 studies, over 20,000 women with ovarian cancer and about 80,000 controls).

The link to the use of fertility medication, such as Clomiphene citrate, has been controversial. An analysis in 1991 raised the possibility that use of drugs may increase the risk of ovarian cancer. Several cohort studies and case-control studies have been conducted since then without demonstrating conclusive evidence for such a link. It will remain a complex topic to study as the infertile population differs in parity from the “normal” population.

Genetics

There is good evidence that in some women genetic factors are important. Carriers of certain mutations of the BRCA1 or the BRCA2 gene are notably at risk. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes account for 5%-13% of ovarian cancers and certain populations (e.g. Ashkenazi Jewish women) are at a higher risk of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer, often at an earlier age than the general population. Patients with a personal history of breast cancer or a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, especially if diagnosed at a young age, may have an elevated risk.

A strong family history of uterine cancer, colon cancer, or other gastrointestinal cancers may indicate the presence of a syndrome known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, also known as Lynch II syndrome), which confers a higher risk for developing ovarian cancer. Patients with strong genetic risk for ovarian cancer may consider the use of prophylactic, i.e. preventative, oophorectomy after completion of childbearing. Australia being member of International Cancer Genome Consortium is leading efforts to map ovarian cancer’s complete genome.

Alcohol

A pooled analysis of ten (10) prospective cohort studies conducted in a number of countries and including 529,638 women found that neither total alcohol consumption nor alcohol from drinking beer, wine or spirits was associated with ovarian cancer risk.” The results of a case-control study in the region of Milan, Italy, “suggests that relatively elevated alcohol intake (of the order of 40 g per day or more) may cause a modest increase of epithelial ovarian cancer risk”. “Associations were also found between alcohol consumption and cancers of the ovary and prostate, but only for 50 g and 100 g a day.” “Statistically significant increases in risk also existed for cancers of the stomach, colon, rectum, liver, female breast, and ovaries.”

Other

A Swedish study, which followed more than 61,000 women for 13 years, has found a significant link between milk consumption and ovarian cancer. According to the BBC, “[Researchers] found that milk had the strongest link with ovarian cancer—those women who drank two or more glasses a day were at double the risk of those who did not consume it at all, or only in small amounts.” Recent studies have shown that women in sunnier countries have a lower rate of ovarian cancer, which may have some kind of connection with exposure to Vitamin D.

Other factors that have been investigated, such as talc use, asbestos exposure, high dietary fat content, and childhood mumps infection, are controversial and have not been definitively proven; moreover, such risk factors may in some cases be more likely to be correlated with cancer in individuals with specific genetic makeups.

What are the Risk Factors?

Doctors cannot always explain why one woman develops ovarian cancer and another does not. However, we do know that women with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop ovarian cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for ovarian cancer:

- Family history of cancer: Women who have a mother, daughter, or sister with ovarian cancer have an increased risk of the disease. Also, women with a family history of cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum may also have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

If several women in a family have ovarian or breast cancer, especially at a young age, this is considered a strong family history. If you have a strong family history of ovarian or breast cancer, you may wish to talk to a genetic counselor. The counselor may suggest genetic testing for you and the women in your family. Genetic tests can sometimes show the presence of specific gene changes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer. - Personal history of cancer: Women who have had cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

- Age over 55: Most women are over age 55 when diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

- Never pregnant: Older women who have never been pregnant have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Menopausal hormone therapy: Some studies have suggested that women who take estrogen by itself (estrogen without progesterone) for 10 or more years may have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Scientists have also studied whether taking certain fertility drugs, using talcum powder, or being obese are risk factors. It is not clear whether these are risk factors, but if they are, they are not strong risk factors.

Having a risk factor does not mean that a woman will get ovarian cancer. Most women who have risk factors do not get ovarian cancer. On the other hand, women who do get the disease often have no known risk factors, except for growing older. Women who think they may be at risk of ovarian cancer should talk with their doctor.

What are the Symptoms of Ovarian Cancer?

The signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer are most of the times absent, but when they exist they are nonspecific. In most cases, the symptoms persist for several months until the patient is diagnosed.

A prospective case-control study of 1,709 women visiting primary care clinics found that the combination of bloating, increased abdominal size, and urinary symptoms was found in 43% of those with ovarian cancer but in only 8% of those presenting to primary care clinics.

Accuracy of symptoms

Two case-control studies, both subject to results being inflated by spectrum bias, have been reported. The first found that women with ovarian cancer had symptoms of increased abdominal size, bloating, urge to pass urine and pelvic pain. The smaller, second study found that women with ovarian cancer had pelvic/abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, and difficulty eating/feeling full. The latter study created a symptom index that was considered positive if any of the six (6) symptoms “occurred >12 times per month but were present for <1 year”. For early-stage disease, they reported a 57% sensitivity and 87% to 90% specificity.

Consensus statement

In 2007, the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and American Cancer Society originated the following consensus statement regarding the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is called a “silent killer” because symptoms were not thought to develop until the disease had advanced and the chance of cure or remission poor. However, the following symptoms are much more likely to occur in women with ovarian cancer than women in the general population. These symptoms include:

- Bloating

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Pain in the back or legs

- Diarrhea, gas, nausea, constipation, indigestion

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

- Urinary symptoms (urgency or frequency)

- Pain during sex

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding

- Trouble breathing

Women with ovarian cancer report that symptoms are persistent and represent a change from normal for their bodies. The frequency and/or number of such symptoms are key factors in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Several studies show that even early stage ovarian cancer can produce these symptoms. Women who have these symptoms almost daily for more than a few weeks should see their doctor, preferably a gynecologist. Prompt medical evaluation may lead to detection at the earliest possible stage of the disease. Early stage diagnosis is associated with an improved prognosis.

Several other symptoms have been commonly reported by women with ovarian cancer. These symptoms include fatigue, indigestion, back pain, pain with intercourse, constipation and menstrual irregularities.

Classification

Ovarian cancer is classified according to the histology of the tumor, obtained in a pathology report. Histology dictates many aspects of clinical treatment, management, and prognosis.

- Surface epithelial-stromal tumour, also known as ovarian epithelial carcinoma, is the most common type of ovarian cancer. It includes serous tumour, endometrioid tumor and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma.

- Sex cord-stromal tumor, including estrogen-producing granulosa cell tumor and virilizing Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor or arrhenoblastoma, accounts for 8% of ovarian cancers.

- Germ cell tumor accounts for approximately 30% of ovarian tumors but only 5% of ovarian cancers, because most germ cell tumors are teratomas and most teratomas are benign. Germ cell tumor tends to occur in young women and girls. The prognosis depends on the specific histology of germ cell tumor, but overall is favorable.

- Mixed tumors, containing elements of more than one of the above classes of tumor histology.

Diagnosis

If you have a symptom that suggests ovarian cancer, your doctor must find out whether it is due to cancer or to some other cause. Your doctor may ask about your personal and family medical history.

You may have one or more of the following tests. Your doctor can explain more about each test:

- Physical exam: Your doctor checks general signs of health. Your doctor may press on your abdomen to check for tumors or an abnormal buildup of fluid (ascites). A sample of fluid can be taken to look for ovarian cancer cells.

- Pelvic exam: Your doctor feels the ovaries and nearby organs for lumps or other changes in their shape or size. A Pap test is part of a normal pelvic exam, but it is not used to collect ovarian cells. The Pap test detects cervical cancer. The Pap test is not used to diagnose ovarian cancer.

- Blood tests: Your doctor may order blood tests. The lab may check the level of several substances, including CA-125. CA-125 is a substance found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells and on some normal tissues. A high CA-125 level could be a sign of cancer or other conditions. The CA-125 test is not used alone to diagnose ovarian cancer. This test is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for monitoring a woman’s response to ovarian cancer treatment and for detecting its return after treatment.

- Ultrasound: The ultrasound device uses sound waves that people cannot hear. The device aims sound waves at organs inside the pelvis. The waves bounce off the organs. A computer creates a picture from the echoes. The picture may show an ovarian tumor. For a better view of the ovaries, the device may be inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasound).

- Biopsy: A biopsy is the removal of tissue or fluid to look for cancer cells. Based on the results of the blood tests and ultrasound, your doctor may suggest surgery (a laparotomy) to remove tissue and fluid from the pelvis and abdomen. Surgery is usually needed to diagnose ovarian cancer. To learn more about surgery, see the “Treatment” section.

Although most women have a laparotomy for diagnosis, some women have a procedure known as laparoscopy. The doctor inserts a thin, lighted tube (a laparoscope) through a small incision in the abdomen. Laparoscopy may be used to remove a small, benign cyst or an early ovarian cancer. It may also be used to learn whether cancer has spread.

A pathologist uses a microscope to look for cancer cells in the tissue or fluid. If ovarian cancer cells are found, the pathologist describes the grade of the cells. Grades 1, 2, and 3 describe how abnormal the cancer cells look. Grade 1 cancer cells are not as likely as to grow and spread as grade 3 cells.

Staging

Ovarian cancer staging is by the FIGO staging system and uses information obtained after surgery, which can include a total abdominal hysterectomy, removal of (usually) both ovaries and fallopian tubes, (usually) the omentum, and pelvic (peritoneal) washings for cytopathology. The AJCC stage is the same as the FIGO stage. The AJCC staging system describes the extent of the primary Tumor (T), the absence or presence of metastasis to nearby lymph Nodes (N), and the absence or presence of distant Metastasis (M).

- Stage I – limited to one or both ovaries

- IA – involves one ovary; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

- IB – involves both ovaries; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; negative washings

- IC – tumor limited to ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, positive washings

- Stage II – pelvic extension or implants

- IIA – extension or implants onto uterus or fallopian tube; negative washings

- IIB – extension or implants onto other pelvic structures; negative washings

- IIC – pelvic extension or implants with positive peritoneal washings

- Stage III – microscopic peritoneal implants outside of the pelvis; or limited to the pelvis with extension to the small bowel or omentum

- IIIA – microscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis

- IIIB – macroscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis less than 2 cm in size

- IIIC – peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis > 2 cm or lymph node metastases

- Stage IV – distant metastases to the liver or outside the peritoneal cavity

Para-aortic lymph node metastases are considered regional lymph nodes (Stage IIIC).

The AJCC/TNM staging system includes three categories for ovarian cancer, T, N and M. The T category contains three other subcategories, T1, T2 and T3, each of them being classified according to the place where the tumor has developed (in one or both ovaries, inside or outside the ovary). The T1 category of ovarian cancer describes ovarian tumors that are confined to the ovaries, and which may affect one or both of them. The sub-subcategory T1a is used to stage cancer that is found in only one ovary, which has left the capsule intact and which cannot be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis. Cancer that has not affected the capsule, is confined to the inside of the ovaries and cannot be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis but has affected both ovaries is staged as T1b. T1c category describes a type of tumor that can affect one or both ovaries, and which has grown through the capsule of an ovary or it is present in the fluid taken from the pelvis. T2 is a more advanced stage of cancer. In this case, the tumor has grown in one or both ovaries and is spread to the uterus, fallopian tubes or other pelvic tissues. Stage T2a is used to describe a cancerous tumor that has spread to the uterus or the fallopian tubes (or both) but which is not present in the fluid taken from the pelvis. Stages T2b and T2c indicate cancer that metastasized to other pelvic tissues than the uterus and fallopian tubes and which cannot be seen in the fluid taken from the pelvis, respectively tumors that spread to any of the pelvic tissues (including uterus and fallopian tubes) but which can also be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis. T3 is the stage used to describe cancer that has spread to the peritoneum. This stage provides information on the size of the metastatic tumors (tumors that are located in other areas of the body, but are caused by ovarian cancer). These tumors can be very small, visible only under the microscope (T3a), visible but not larger than 2 centimeters (T3b) and bigger than 2 centimeters (T3c).

This staging system also uses N categories to describe cancers that have or not spread to nearby lymph nodes. There are only two N categories, N0 which indicates that the cancerous tumors have not affected the lymph nodes, and N1 which indicates the involvement of lymph nodes close to the tumor.

The M categories in the AJCC/TNM staging system provide information on whether the ovarian cancer has metastasized to distant organs such as liver or lungs. M0 indicates that the cancer did not spread to distant organs and M1 category is used for cancer that has spread to other organs of the body.

The AJCC/TNM staging system also contains a Tx and a Nx sub-category which indicates that the extent of the tumor cannot be described because of insufficient data, respectively the involvement of the lymph nodes cannot be described because of the same reason.

The ovarian cancer stages are made up by combining the TNM categories in the following manner:

- Stage I: T1+N0+M0

- IA: T1a+N0+M0

- IB: T1b+N0+M0

- IC: T1c+N0+M0

- Stage II: T2+N0+M0

- IIa: T2a+N0+M0

- IIB: T2b+N0+M0

- IIIC: T2c+N0+M0

- Stage III: T3+ N0+M0

- IIIA: T3a+ N0+M0

- IIIB: T3b+ N0+M0

- IIIC: T3c+ N0+M0 or Any T+N1+M0

- Stage IV: Any T+ Any N+M1

Ovarian cancer, as well as any other type of cancer, is also graded, apart from staged. The histologic grade of a tumor measures how abnormal or malignant its cells look under the microscope. There are four grades indicating the likelihood of the cancer to spread and the higher the grade, the more likely for this to occur. Grade 0 is used to describe non-invasive tumors. Grade 0 cancers are also referred to as borderline tumors. Grade 1 tumors have cells that are well differentiated (look very similar to the normal tissue) and are the ones with the best prognosis. Grade 2 tumors are also called moderately well differentiated and they are made up by cells that resemble the normal tissue. Grade 3 tumors have the worst prognosis and their cells are abnormal, referred to as poorly differentiated.

Methods of Treatment

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. Most women have surgery and chemotherapy. Rarely, radiation therapy is used.

Cancer treatment can affect cancer cells in the pelvis, in the abdomen, or throughout the body:

- Local therapy: Surgery and radiation therapy are local therapies. They remove or destroy ovarian cancer in the pelvis. When ovarian cancer has spread to other parts of the body, local therapy may be used to control the disease in those specific areas.

- Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Chemotherapy can be given directly into the abdomen and pelvis through a thin tube. The drugs destroy or control cancer in the abdomen and pelvis.

- Systemic chemotherapy: When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein, the drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy or control cancer throughout the body.

You may want to know how treatment may change your normal activities. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each woman, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option for women with all stages of ovarian cancer. The section on “The Promise of Cancer Research” has more information about clinical trials.

Surgery

The surgeon makes a long cut in the wall of the abdomen. This type of surgery is called a laparotomy. If ovarian cancer is found, the surgeon removes:

- both ovaries and fallopian tubes (salpingo-oophorectomy)

- the uterus (hysterectomy)

- the omentum (the thin, fatty pad of tissue that covers the intestines)

- nearby lymph nodes

- samples of tissue from the pelvis and abdomen

If the cancer has spread, the surgeon removes as much cancer as possible. This is called “debulking” surgery.

If you have early Stage I ovarian cancer, the extent of surgery may depend on whether you want to get pregnant and have children. Some women with very early ovarian cancer may decide with their doctor to have only one ovary, one fallopian tube, and the omentum removed.

You may be uncomfortable for the first few days after surgery. Medicine can help control your pain. Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your doctor or nurse. After surgery, your doctor can adjust the plan if you need more pain relief.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for each woman. You will spend several days in the hospital. It may be several weeks before you return to normal activities.

If you haven’t gone through menopause yet, surgery may cause hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and night sweats. These symptoms are caused by the sudden loss of female hormones. Talk with your doctor or nurse about your symptoms so that you can develop a treatment plan together. There are drugs and lifestyle changes that can help, and most symptoms go away or lessen with time.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to kill cancer cells. Most women have chemotherapy for ovarian cancer after surgery. Some women have chemotherapy before surgery.

Usually, more than one drug is given. Drugs for ovarian cancer can be given in different ways:

- By vein (IV): The drugs can be given through a thin tube inserted into a vein.

- By vein and directly into the abdomen: Some women get IV chemotherapy along with intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy. For IP chemotherapy, the drugs are given through a thin tube inserted into the abdomen.

- By mouth: Some drugs for ovarian cancer can be given by mouth.

Chemotherapy is given in cycles. Each treatment period is followed by a rest period. The length of the rest period and the number of cycles depend on the anticancer drugs used.

You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor’s office, or at home. Some women may need to stay in the hospital during treatment.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on which drugs are given and how much. The drugs can harm normal cells that divide rapidly:

- Blood cells: These cells fight infection, help blood to clot, and carry oxygen to all parts of your body. When drugs affect your blood cells, you are more likely to get infections, bruise or bleed easily, and feel very weak and tired. Your health care team checks you for low levels of blood cells. If blood tests show low levels, your health care team can suggest medicines that can help your body make new blood cells.

- Cells in hair roots: Some drugs can cause hair loss. Your hair will grow back, but it may be somewhat different in color and texture.

- Cells that line the digestive tract: Some drugs can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Ask your health care team about medicines that help with these problems.

Some drugs used to treat ovarian cancer can cause hearing loss, kidney damage, joint pain, and tingling or numbness in the hands or feet. Most of these side effects usually go away after treatment ends.

You may find it helpful to read NCI’s booklet Chemotherapy and You: A Guide to Self-Help During Cancer Treatment.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. A large machine directs radiation at the body.

Radiation therapy is rarely used in the initial treatment of ovarian cancer, but it may be used to relieve pain and other problems caused by the disease. The treatment is given at a hospital or clinic. Each treatment takes only a few minutes.

Side effects depend mainly on the amount of radiation given and the part of your body that is treated. Radiation therapy to your abdomen and pelvis may cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or bloody stools. Also, your skin in the treated area may become red, dry, and tender. Although the side effects can be distressing, your doctor can usually treat or control them. Also, they gradually go away after treatment ends.

NCI provides a booklet called Radiation Therapy and You: A Guide to Self-Help During Cancer Treatment.

Supportive care

Ovarian cancer and its treatment can lead to other health problems. You may receive supportive care to prevent or control these problems and to improve your comfort and quality of life.

Your health care team can help you with the following problems:

- Pain: Your doctor or a specialist in pain control can suggest ways to relieve or reduce pain. More information about pain control can be found in the NCI booklets Pain Control: A Guide for People with Cancer and Their Families, Get Relief from Cancer Pain, and Understanding Cancer Pain.

- Swollen abdomen (from abnormal fluid buildup called ascites): The swelling can be uncomfortable. Your health care team can remove the fluid whenever it builds up.

- Blocked intestine: Cancer can block the intestine. Your doctor may be able to open the blockage with surgery.

- Swollen legs (from lymphedema): Swollen legs can be uncomfortable and hard to bend. You may find exercises, massages, or compression bandages helpful. Physical therapists trained to manage lymphedema can also help.

- Shortness of breath: Advanced cancer can cause fluid to collect around the lungs. The fluid can make it hard to breathe. Your health care team can remove the fluid whenever it builds up.

- Sadness: It is normal to feel sad after a diagnosis of a serious illness. Some people find it helpful to talk about their feelings. See the “Sources of Support” section for more information.

Nutrition and physical activity

It’s important for women with ovarian cancer to take care of themselves. Taking care of yourself includes eating well and staying as active as you can.

You need the right amount of calories to maintain a good weight. You also need enough protein to keep up your strength. Eating well may help you feel better and have more energy.

Sometimes, especially during or soon after treatment, you may not feel like eating. You may be uncomfortable or tired. You may find that foods do not taste as good as they used to. In addition, the side effects of treatment (such as poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, or mouth sores) can make it hard to eat well. Your doctor, a registered dietitian, or another health care provider can suggest ways to deal with these problems. Also, the NCI booklet Eating Hints for Cancer Patients has many useful ideas and recipes.

Many women find they feel better when they stay active. Walking, yoga, swimming, and other activities can keep you strong and increase your energy. Whatever physical activity you choose, be sure to talk to your doctor before you start. Also, if your activity causes you pain or other problems, be sure to let your doctor or nurse know about it.

Drugs rating:

| Title | Votes | Rating | ||

| 1 | Adriamycin (Doxorubicin) | 11 |

|

(8.9/10) |

| 2 | Cytoxan (Cyclophosphamide) | 42 |

|

(7.0/10) |

| 3 | Doxil (Doxorubicin Liposomal) | 9 |

|

(7.0/10) |

| 4 | Avastin (Bevacizumab) | 13 |

|

(6.8/10) |

| 5 | Taxol (Paclitaxel) | 13 |

|

(6.0/10) |

| 6 | Alkeran (Melphalan) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 7 | Etopophos (Etoposide) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 8 | Toposar (Etoposide) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 9 | Hexalen (Altretamine) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 10 | VePesid (Etoposide) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 11 | Ethyol (Amifostine) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 12 | Cosmegen (Dactinomycin) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 13 | Gemzar (Gemcitabine) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 14 | Thioplex (Thiotepa) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 15 | Thiotepa | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 16 | Neosar (Cyclophosphamide) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 17 | Onxol (Paclitaxel) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 18 | Paraplatin (Carboplatin) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 19 | Platinol (Cisplatin) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

| 20 | Hycamtin (Topotecan) | 0 |

|

(0/10) |

Prognosis

Ovarian cancer usually has a poor prognosis. It is disproportionately deadly because it lacks any clear early detection or screening test, meaning that most cases are not diagnosed until they have reached advanced stages. More than 60% of patients presenting with this cancer already have stage III or stage IV cancer, when it has already spread beyond the ovaries. Ovarian cancers shed cells into the naturally occurring fluid within the abdominal cavity. These cells can then implant on other abdominal (peritoneal) structures, included the uterus, urinary bladder, bowel and the lining of the bowel wall forming new tumor growths before cancer is even suspected.

The five-year survival rate for all stages of ovarian cancer is 45.5%. For cases where a diagnosis is made early in the disease, when the cancer is still confined to the primary site, the five-year survival rate is 92.7%.

Complications

- Spread of the cancer to other organs

- Progressive function loss of various organs

- Ascites (fluid in the abdomen)

- Intestinal obstructions

These cells can implant on other abdominal (peritoneal) structures, including the uterus, urinary bladder, bowel, lining of the bowel wall (omentum) and, less frequently, to the lungs.

Follow-up

You will need regular checkups after treatment for ovarian cancer. Even when there are no longer any signs of cancer, the disease sometimes returns because undetected cancer cells remained somewhere in your body after treatment.

Checkups help ensure that any changes in your health are noted and treated if needed. Checkups may include a pelvic exam, a CA-125 test, other blood tests, and imaging exams.

If you have any health problems between checkups, you should contact your doctor.

You may wish to read the NCI booklet Facing Forward Series: Life After Cancer Treatment. It answers questions about follow-up care and other concerns. It also suggests ways to talk with your doctor about making a plan of action for recovery and future health.

Prevention

There are a number of ways to reduce or eliminate the risk of ovarian cancer. Pregnancy before the age of 25 as well as breastfeeding provides some reduction in risk. Tubal ligation and hysterectomy reduce the risk and removal of both tubes and ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) dramatically reduces the risk of not only ovarian cancer but breast cancer also. The use of oral contraceptives (birth control pills) for five years or more decreases the risk of ovarian cancer in later life by 50%.

Tubal ligation is believed to decrease the chance of developing ovarian cancer by up to 67% while a hysterectomy may reduce the risk of getting ovarian cancer by about one-third. Moreover, according to some studies, analgesics such as acetaminophen and aspirin seem to reduce one’s risks of developing ovarian cancer. Yet, the information is not consistent and more research needs to be carried on this matter.

Screening

Routine screening of the general population is not recommended by any professional society. This includes the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

No trial has shown improved survival for women undergoing screening.

Screening tests include the CA-125 marker, transvaginal ultrasound, and combinations of markers such as OvaSure (LabCorp). A definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision of the ovaries and fallopian tubes, so a positive screening test must be followed up by surgery.

The purpose of screening is to discover ovarian cancer in early stages, when it is more curable, on the hypothesis that early-stage cancer develops into later-stage cancer. However, it is not known whether early stage ovarian cancer evolves to later stage cancer, or whether stage III (peritoneal cavity involvement) arises as a diffuse process.

The goal of ovarian cancer screening is to detect ovarian cancer at stage I. Several large studies are ongoing, but none have recommended screening. In 2009, however, Menon et al. reported from the UKCTOCS that utilizing mutimodal screening, in essence first performing annual CA-125 testing, followed by ultrasound imaging on the secondary level, the positive predictive value was 35.1% for primary invasive epithelial ovarian and tubal carcinoma, making such screening feasible. However, it remains to be seen if such screening is effective to reduce mortality.